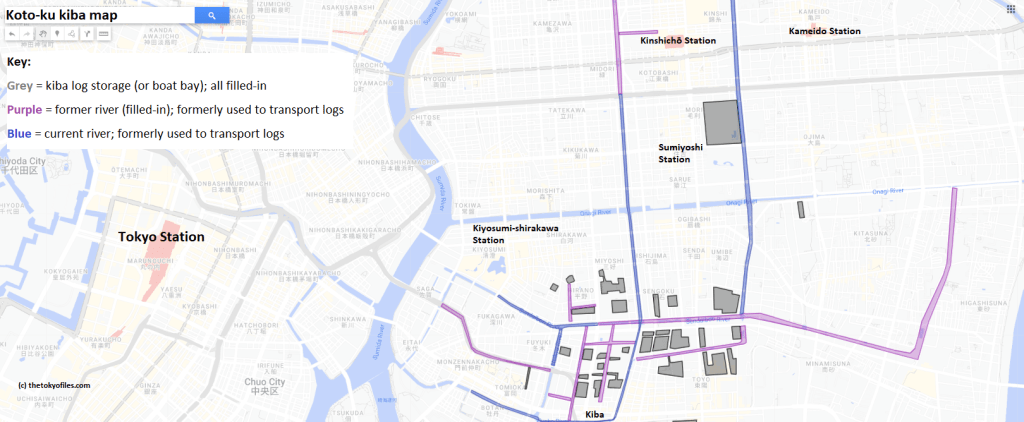

Companion map for this post:

I. Background

Previously I posted a deep dive on how Tokyo’s upscale Ginza neighborhood was once crisscrossed with canals that weren’t filled until the decades following WW2. While I’ve never experienced the old Ginza, seeing old photographs make it clear just how different the area would have felt.

We turn our attention to Koto-ku, one of the central 23 wards of Tokyo, a section of the city that to this day is covered by a network of rivers/canals, but which until a few decades ago had even more water.

II. From Koto to Kiba

The name Koto 江東 means “east of the river”, which fits nicely as this land has long been defined by its relationship to water *. A nice introduction to Koto-ku history can be found at the Nakagawa Funabansho Museum. Background information from the museum website:

“The majority of Koto-ku sits on reclaimed land built up since the Edo period. Many canals were dug along with the landfill construction and these canals have made a big impact on the industry and culture of Koto-ku. The Fukagawa Waterway Station, whose function was to check waterway-bound trades, originally stood by the Onagigawa waterway at the mouth of the Sumida river…The station checked people and goods brought by barges into Edo; this included monitoring the flow of weapons to identify potential wars against the Shogunate. The station also checked the flow of women leaving Edo, as the Shogunate would take hostage the wife of each feudal lord (daimyo) in Edo and forbid her from going home.”

* Today’s administrative ward of Koto-ku was formed in 1947 from the old Tokyo City districts of Fukagawa and Jōtō, but for purposes of this post I will just refer to Koto-ku.

To provide broader context, below is a map of most of Tokyo’s 23 main wards *. Koto-ku is essentially a river delta, formed from the sediment left by the Sumida River as it emptied into Tokyo Bay. In the early 20th century, the Arakawa River Floodway was added, and Koto-ku is now nestled between both rivers.

*Plus parts of Chiba Prefecture at the right: Matsudo and Ichikawa, and Saitama Prefecture’s Wako at top-left.

While Koto-ku’s land began as silt, it has steadily been augmented over the centuries by extensive land reclamation. The following map shows the boundaries of the shoreline as it was in 1594 and in 1608, as compared to 1880. The reclamation has continued since.

Reclaimed land is prone to flood risk by nature of its low elevation, as illustrated by this storm surge map. The majority of the lowest-lying land is in Koto-ku, indicated by dark pink.

Of historical note, Koto-ku was among the hardest hit sections of from the Allied Bombing of Tokyo in 1945, as seen in the red parts of the fire-damage map (below, left), and the black sections of the bomb-damage map, below-right. As a result of this history, Koto-ku is home to the The Center of the Tokyo Raid and War Damages (map).

Over the last several decades, Koto-ku has transformed itself into an appealing place to live. This quote from Metropolis Magazine sums it up nicely:

“Koto is a surprising candidate to beat many of Tokyo’s most famous cities for the #2 spot. However, it rises to the top based on strengths across all categories. It boasts above-average scores for safety, transportation, crowds and green space, and has average scores for diversity, English-language infrastructure, cultural attractions and resident satisfaction. There’s no doubt that Koto ranks as an attractive, low-key place to live with immediate access to everything Tokyo has to offer.”

Koto-ku’s appeal is at least in part influenced by Tokyo’s shift in housing preference, with more homeowners willing to pay a premium yen for brand-new condos. This passage provides some background:

But let’s turn our attention to something more fun: logs!

III. Spotlight on Lumber

Where there is water there is commerce, and for Koto-ku one of the more interesting and long-lasting commercial ventures was the lumber trade, which, during the Edo-era, settled in today’s Koto-ku in 1703 when the area was designated as 木場町 (Kiba-machi, or Kiba Town) (source) – the lumber trade was moved here due to concerns over fire risk in the more established parts of Edo on the other side of the river (source).

Logs from far upstream made their way to Koto-ku’s maze of canals, eventually ending up in kiba (lumber ponds) 木場 where they would be processed by sawmills and sold. As recently as the 1960s dozens of kiba were in use, concentrated around the area north of Kiba Station and today’s Kiba Park. Starting in 1969 the log trade began moving about 3 kilometers south to Shin-Kiba (New Kiba), where the logs were stored until at least around 1990, as seen via aerial photos:

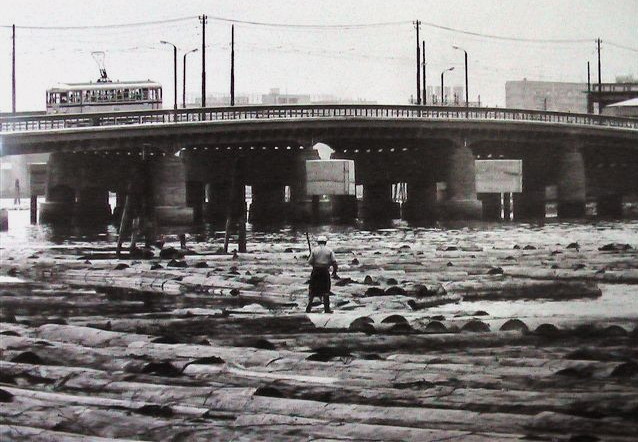

Old photos of the log trade in Koto-ku are wild. Here’s a man tending to his flock of logs in 1965 near Aioi Bridge 相生橋 (which connect Koto-ku to Tsukuda 佃, an equally water-bound area which is part of Chuo-ku.)

Here, in 1972, are a couple of dudes casually piloting logs under the Toyozumi-bashi 豊住橋 (map) in Koto-ku (source), which is in the heart of the old kiba district. In this, as in the above photo, we get to enjoy a sighting of one of the many Toden streetcars that covered most of Tokyo.

My favorite picture is this one, taken in 1974, titled 深川木場の貯木場 (Fukagawa Kiba Lumberyard) (source 1; source 2), which is I believe is located in the vicinity of today’s Kiba Park in Koto-ku.

And one more: 深川木場の材木問屋街 Fukagawa Lumber wholesale District, 1971 (source):

IV. Maps and Comparisons

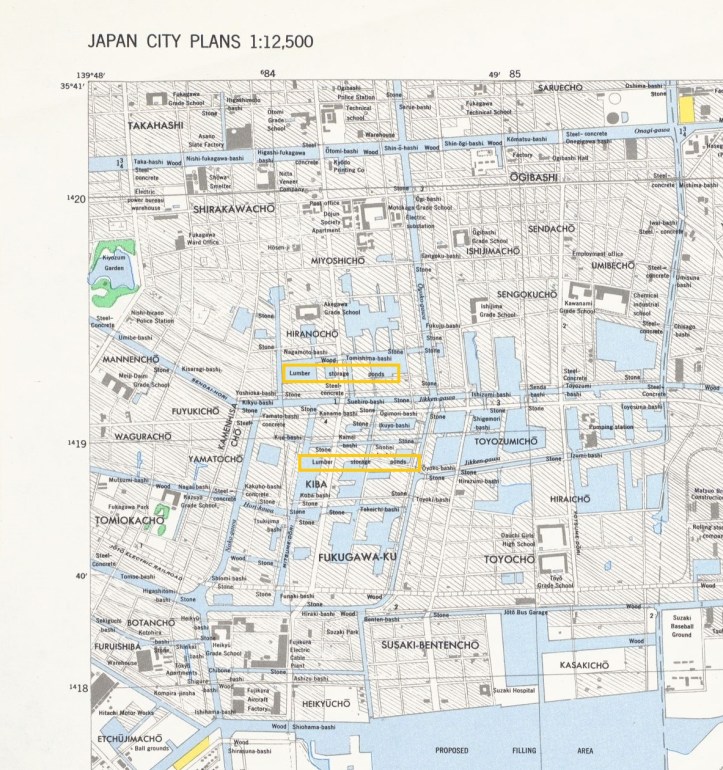

For those interested in the exact location of the old kiba, a great place to start are the maps from the U.S. Army Map Service, 1945-1946. The Koto-ku kiba can be seen in maps #9 and #13. The eastern half of map #13, excerpted below, shows the bottom of Koto-ku, with kiba labeled as “lumber storage ponds” (source, map13). The center of this excerpt is the intersection of two rivers, the north-south Ooyokogawa 大横川 and the east-west Sendaiborigawa 仙台堀川 (map), just to the east of today’s Kiba Park.

The section of map at bottom, labeled “Proposed Filling Area” has been reclaimed and is now 深川車両基地 (Fukagawa Train Depot), used for Tokyo Metro’s trains; (pics).

If you don’t trust maps, take a look at this aerial photo, circa 1945-1950, which is zoomed-in on the center of the map above (source). I’ve indicated in yellow boxes some of the various kiba. It’s fun to play around with the aerial photo data to locate as many kiba as you can. You can also spot thousands of logs lining the rivers and canals.

By the 1960s, many of these kiba have been filled-in, as seen in aerial photographs (center of this map: here).

Once filled-in, many of the kiba became public parks, including the sizable Kiba Park and Sakue Park.

Kiba park

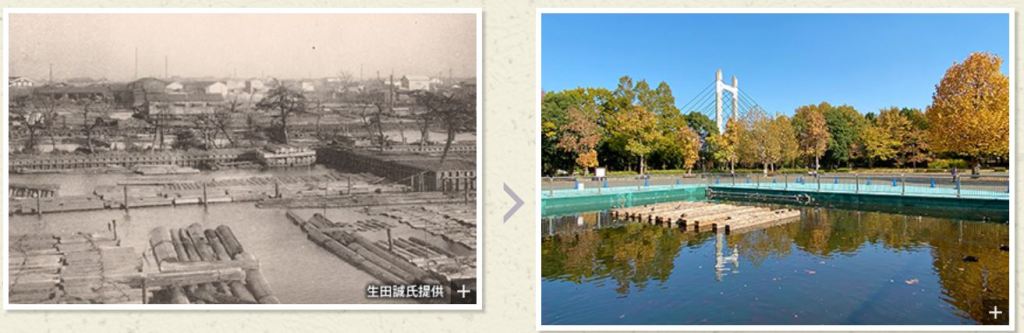

Here’s a then-and-now comparison from the extremely helpful and comprehensive Sumitomo Mitsui Trust website, which has then-and-now photos from all over Tokyo.

Sarue Park

North of map #13 is #9 (source, map 9), which includes the rest of Koto-ku as well as Sumida-ku to the north. In the excerpt below I’ve indicated three things: Kameido Station at right, “Forestry bureau log dump” at center, with Sarue Park immediately to its south.

Today’s “log dump” is now Sarue Park 猿江恩賜公園 (aka Sarue-onshi Park). Of note, the park has a “Miniature lumberyard”, i.e. mini-kiba ミニ木蔵, which honors the park’s original land-use.

Shin-Kiba

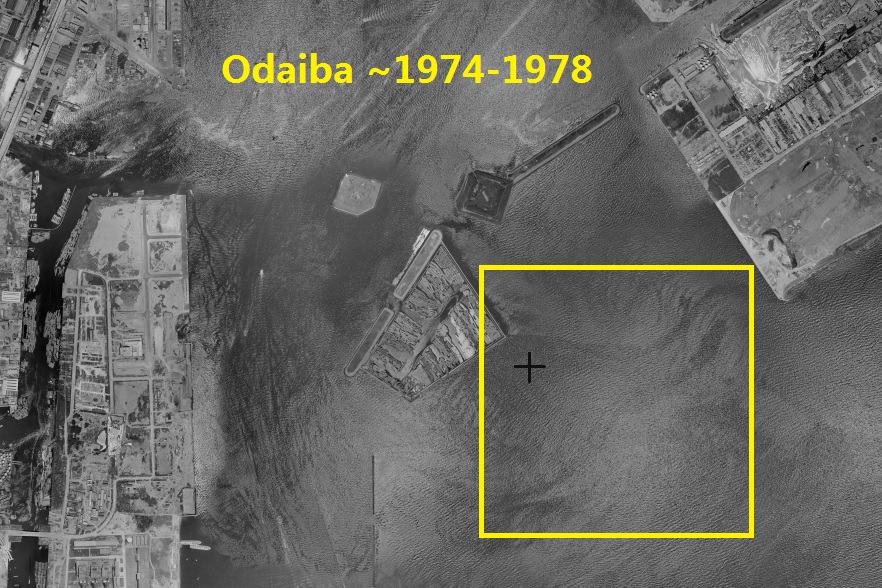

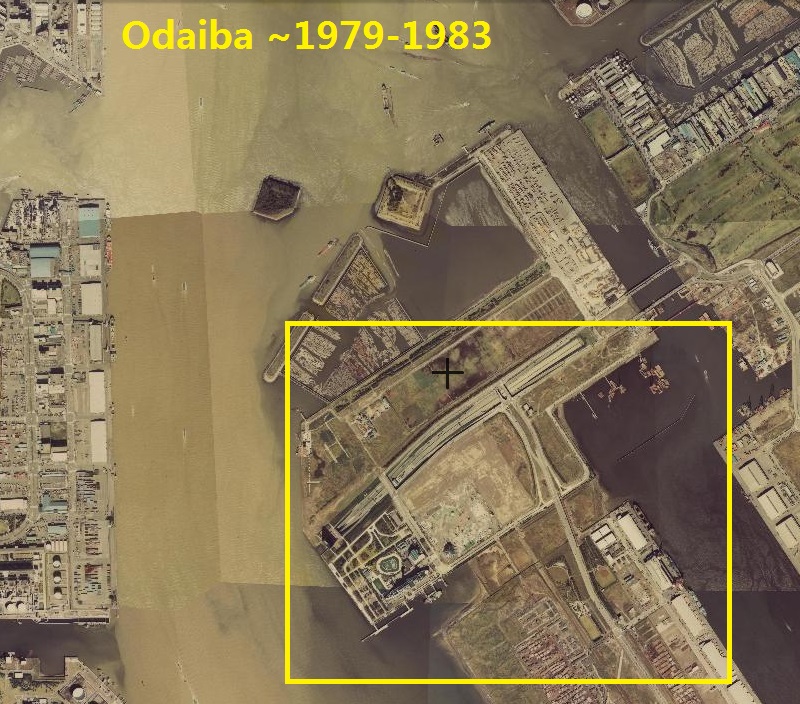

As noted earlier, over the decades the kiba moved south, as more land was being reclaimed from Tokyo Bay. The following shows the evolution of this area from ~1945 to ~1975. About 10 years later, Shin-Kiba Station 新木場駅 would open (at the bottom of the photo).

I noted this kiba in an earlier post about Tatsumi Danchi 辰巳団地. Today the water for this kiba is crossed by the JR Sunamachi Canal Bridge JR砂町運河橋梁 (map).

V. Kiba in art

How could I take so long to get to the best part: kiba-inspired art. I’m sure there’s more out there, but here are two I’ve known of for a while:

“Lumberyards at Kiba in the snow”, aka Fukagawa Ward, Kiba River 深川区・木場の河筋 (1940) by Koizumi Kishio.

And Hasui Kawase’s 川瀬巴水 (1883-1957) “Evening at the Lumber Yards of Kiba” 木場の夕暮 (1920), which refers to old lumberyards of current day Kiba, Koto-ku. (See also Kawase’s “The Shinagawa Offing” 品川沖).

I also get a kick out of seeing kiba in movies, such as in Shuji Tereyama’s The Boxer ボクサー (1977) (photo), or in this incredible scene from Cruel Story of Youth (1960) 青春残酷物語.

This scene was filmed at the large kiba that sits next to the reclaimed land that is now Odaiba, which you can read about separately.

VI. Items of Interest in this area

The following are a list of museums and walking paths / places of interest that are worth visiting of you want to explore this part of Koto-ku (and Sumida-ku).

Museums

(1) Fukagawa Edo Museum 深川江戸資料館 (map): recreation of an Edo-era townscape from the Fukugawa neighborhood.

(2) Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) 東京都現代美術館(MOT) (map): one of the best art museums in Tokyo (if you like contemporary art).

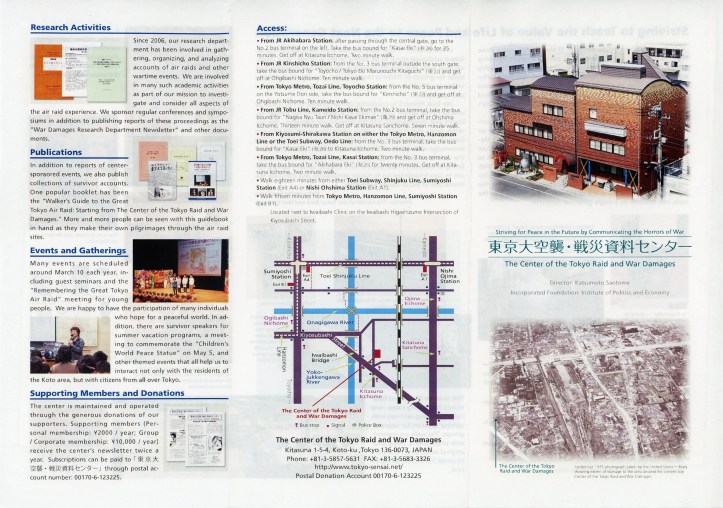

(3) The Center for the Tokyo Raids and War Damage 東京大空襲・戦災資料センター (map): the center’s mission is to promote peace through studying the horrors of war, with particular focus on the Tokyo firebombings (which are overshadowed by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima 広島 and Nagasaki 長崎).

(4) Nakagawa Funabansho Museum 中川船番所資料館 / 江東区中川船番所資料館 (map): main room includes a replica of a fisherman’s hut and a fishing boat, with a large floor to ceiling mural of life in pre-industrial Koto-ku.

(5) Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall 第五福竜丸展示館 (map): this museum consists almost entirely of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (“Lucky Dragon 5”), a Japanese fishing boat that was subject to the fallout of an American nuclear test in 1954. The ship’s crew of 23 suffered acute radiation syndrome (ARS), with one member eventually dying. The ship has been a museum since 1976. It is located in Yumenoshima park, a 10-minute walk from Shin-kiba station.

(6) Wood & Plywood Museum 木材・合板博物館 (map)

(7) Meiji-maru 明治丸 (map): museum boat at the Tokyo University of Marine Science campus in Etchujima (Koto-ku). Built in Glasgow in 1873 for the Japan’s lighthouse service. In 1876, Emperor Meiji sailed on the ship from Aomori to Hakodate and Hakodate to Yokohama.

(8) Tobacco & Salt Museum (Sumida-ku) (map): situated next to the delightful Oyokogawa Water Park (see below). The tobacco section has a surprisingly delightful pipe collection, and the salt section has a fascinating display on 枝条架 (branch racks), formerly used in the cultivation of sea salt. (Note – during the Edo era salt was transported into the city via Onagigawa Salt Road: Onagigawa River Shio-no-michi 小名木川しおのみち.)

Walking paths, etc.

(A) Sky Tree: you know, that really tall tower that’s not Tokyo Tower. Next to it is a great park for children: (B) Oyokogawa River Park 大横川親水公園, aka Oyokogawa Shinsui Park, Tokyo Skytree View (map):

South of Sky tree is (C) Oyokogawa Water Park 大横川親水公園 trail, a 1.8 kilometer path that built over the remains of a section of the Ooyokogawa River 大横川. The river continues south a little past Kinsicho Station.

(D) Onagigawa Clover Bridge (map): a fairly unique four-cornered bridge that gives you a close connection to the water.

(E) Just south of the Clover Bridge is Yokojukken River Water Park 横十間川親水公園 / ヨコジュッケンガワシンスイコウエン (map), which makes me want to be a kid again.

(F) South of here is the extensive Sendaibori River Park 仙台堀川公園, which is full of interesting nooks and crannies like a fishing facility, rice cultivation park, and other diversions. The northern end starts at the Onagigawa River (map), and the path continues in a backwards L shape south and west, ending near Kiba Park (map).

(G) To the east side of Sendaibori River Park is Sunamachi Ginza Shotengai (Shopping District) 砂町銀座商店街 (map): this is interesting because most shotengai develop near train stations (or sometimes temples), but this one is sort of “in the middle of noweher” compare to a typical shotengai. (I plan to read more about this area’s history.)

(H) Lastly, Hachimanbori Walk 八幡堀遊歩道 and Hachimanbori Bride 八幡橋 (旧弾正橋) (map): this short section of former canal / kiba has been filled-in but retain its bridge, which I assume was the one in place at the time when the canal was filled.

VII. Related items

Odaiba: as mentioned earlier, the waters near Odaiba were used as a kiba, as seen here in the 1970s. The kiba is at the top-left of the yellow box.

Onagigawa Station 小名木川駅 (aka Sunamachi Freight Yards), which was in use from 1929-2000. Now the site of Ito-Yokado Ario Kitasuna shopping plaza, this facility connected freight rail with small freight boats used in the Koto-ku canal system. The boat bay has since been filled-in.

Appendix

Kiba no Kakunori (Log-rolling Performance)

- Kiba no Kakunori Preservation Society 木場角乗保存会

- Background information

- Background information and photos 木場の角乗り (Japanese)

- Practice session:

Aerial photos

Areas of interest

- Koto-ku Rice Paddy parr 江東区民の田んぼ (map)

- Sightseeing boat tours, etc.: http://www.sawaura.co.jp/

Sources:

- History of kiba per a wood veneer company (株式会社丸増ベニヤ商会) (Japanese).

- https://tokyobojo.exblog.jp/22543317/

- Tokyo’s Growing Yen for High-Rise Apartments (Wall Street Journal)

See also:

- Maps: Koto-ku rivers and canals 江東内部河川地図

- Koto-ku walking map: Onagigawa & Higashi-Ojima

- Maps of Edo-era Tokyo: a focus on water

- 1858 An0tique Japanese Map of Fukagawa 深川, Kōtō 江東区 Ward, Tokyo 東京 Japan 日本

Information about the Koto Delta:

- Urban environmental structure on Koto delta area seen through transition of artificial topographic change

- A Study on Appropriate Human Evacuation Plan in Koto Delta Area during Large-scale Flood

- A study on the slum clearance redevelopment project and the community design project for disaster in Koto-delta (PDF)

- Lowland Rivers Projects in Tokyo

[…] basin’ 貯木場, a variation of ‘lumberyard’ 貯木. For more information see: The floating world of floating logs: the kiba of Koto-ku 江東区の木場 and Odaiba, then & now: a visual […]