Introduction

The two toilets shown above are typical of Japan: one is playfully guarded by Godzilla; the other has a faucet used for hand-washing that also refills the tank. This simple water-saving design is completely foreign to a visiting American. My friends refused to use the toilet/faucet, convinced that the water was “dirty”.

The “water-saving toilet” 節水型トイレ is an illustration of Japan’s intricate relationship with water. A stroll through Tokyo will reveal old water towers, tall levees, and extensive canals. Tokyo’s water infrastructure dates back to the early days of Edo, but it wasn’t until after WWII that its water became both plentiful AND safe. The American occupation led to a variety of public health improvements including immunization, vaccination, and cleaner water supplies; these are credited with preventing the deaths of 2.1 million Japanese (A). Until this time, water often flowed via uncovered aqueducts, allowing the spread of water-borne diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, and cholera. Japan is now a leader in water technology, helping other nations achieve clean, stable water supplies. Japanese corporations and governmental bodies have for years been involved in water projects throughout the world, such as planned projects in Yangon, the largest city in the newly-opened Myanmar *.

* Broken link: www jica.go jp/myanmar/english/office/topics/press180510 html

As I write these words I look at the kitchen sink and count my blessings that I can drink the water that comes out. Worldwide, between 768 million and 780 million people do not have access to clean water, and 2.5 billion people don’t have proper sanitation. Japan would have been included in these statistics until after World War II, which is a testament to how far Japan has come, and serves as a practical example for countries who seek to improve their water supplies. I am frequently reminded of Tokyo’s water history during my long rambles through Tokyo. Here are some of the things I’ve seen:

Tokyo’s Water Infrastructure:

1. Tamagawa-josui 玉川上水

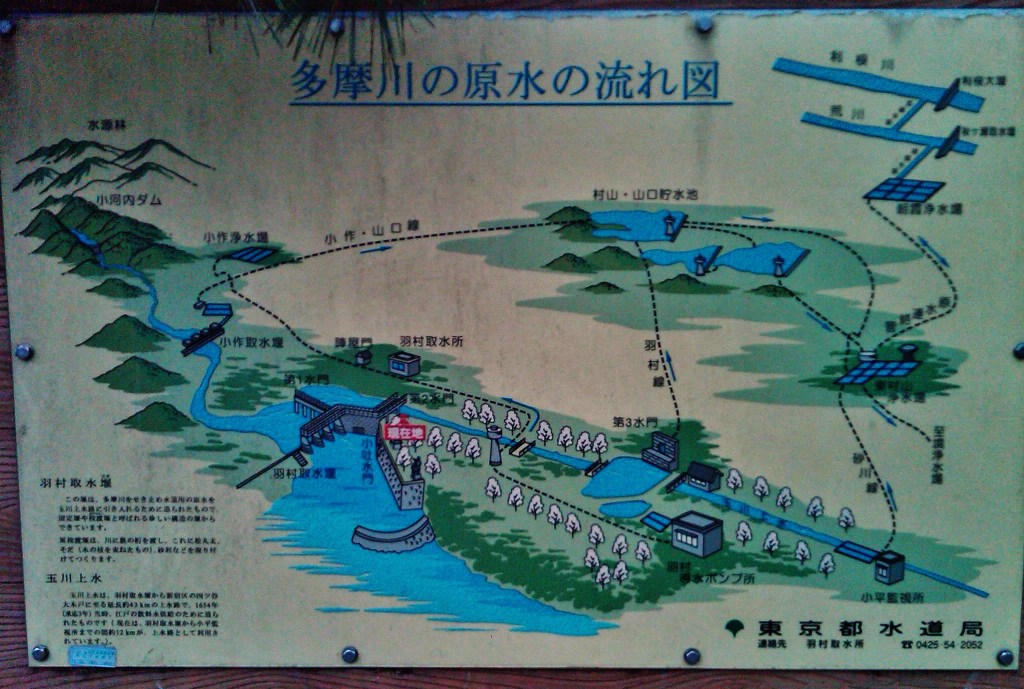

While Tokyo’s water may not have been clean, at least it was somewhat plentiful, thanks to the foresight of the Tokugawa shogunate. When Edo became capital of Japan in 1603, the city expanded and the need for water increased. To address growing needs, canals such as the Kandagawa river 神田川 were built. By mid-17th century construction began on the more ambitious Tamagawajosui 玉川上水, which diverts water from the Tamagawa river in the western Tokyo town of Homura 羽村to Edo (Tokyo), spanning a distance of around 25 miles. For a wonderful display of the canal and river systems of Tokyo, I recommend the Tokyo Waterworks Historical Museum 東京都水道歴史館 which also displays an old wooden pipe system that was uncovered during the construction of a building in central Tokyo. (If you are more interested in dirty water, you may consider visiting the Museum of the Sewerage ふれあい下水道館.)

The Tamagawa-josui still exists, a discovery that still thrills me. In October of 2011 I was wandering from Kodaira 小平市 towards Kokubunji 国分寺市 when I crossed over an extremely straight stream, bordered on both sides by a dirt path. I later learned from a government tourism website that this was the Tamagawajosui one of the “13 ways to understand Tokyo’s urban infrastructure”.

A month later I had an unexpected day off from work – it was Labour Thanksgiving Day 勤労感謝の日 – so I set off for Hamura to see the source of the canal. Hamura sits on the northeast side of the Tamagawa river, which, at this point, is wide and rocky, and bordered by low hills. The river travels southeast, where it empties into Tokyo Bay in Kawasaki. The people of Edo, however, required the water to run due east, and it was here that the waters are diverted by the Hamura diversion weir 羽村取水堰 and form the start of the Tamagawajosui canal.

Over the course of three separate trips I walked the length of the josui, coming across interesting sights such as the Hitachi Aircraft substation, a building that was strafed by American gunfire during WW2. The canal itself, is beautiful and tranquil; it is a 25-mile ribbon of nature that unfolds across the otherwise grey urban framework. The meditative rhythm of walking next to the canal transported me 400-years into the past, making this one of my favorite Tokyo adventures. (B)

Tamagawa josui map (source)

2. Steep rivers

Despite generous rainfalls, water in Japan has proved troublesome due to flooding. As 70% of the land is mountainous, the steep streams all run towards a limited drainage area, which is especially dangerous during rainy season. One of the rivers that continually caused flooding in Tokyo was the Arakawa River 荒川. In response to massive flooding 1910, the government embarked on a project to divert part of the river into a man-made channel. The project was led by Akira Aoyama 青山士(あきら), recently returned from Panama, where he had been the only Japanese national working on that project. In 1924, a major element of the project was completed, which is known variously as: the Arakawa lock, Old Iwabuchi Water Gate, Red Sluice Gate, Iwabuchi sluice gate 岩淵水門, Akasuimon 赤水門 (map).

While the Old Red Gate is now purely decorative, a new gate takes its place, along with the many other flood gates that protect Tokyo from continual flooding during typhoon season. You’ve probably seen some of these flood gates if you’ve spent any time on the Arakawa or Sumidagawa rivers.

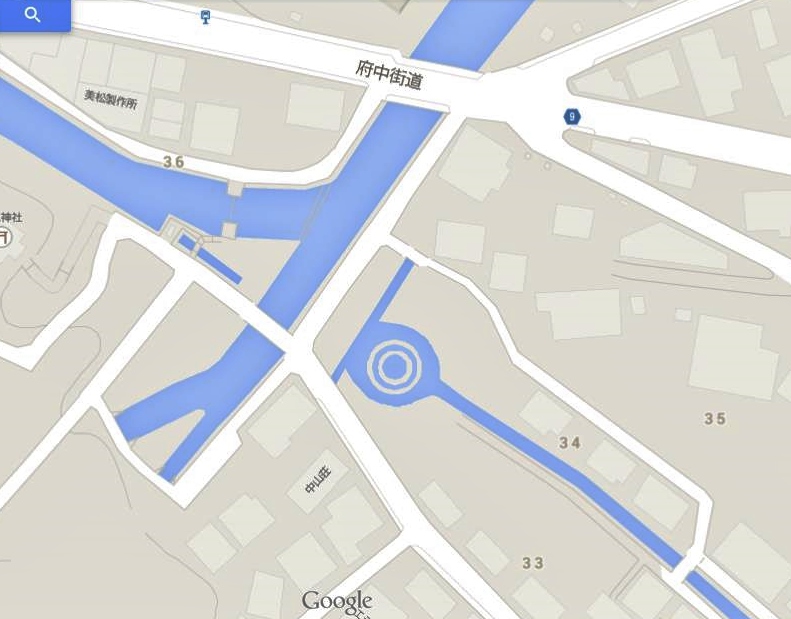

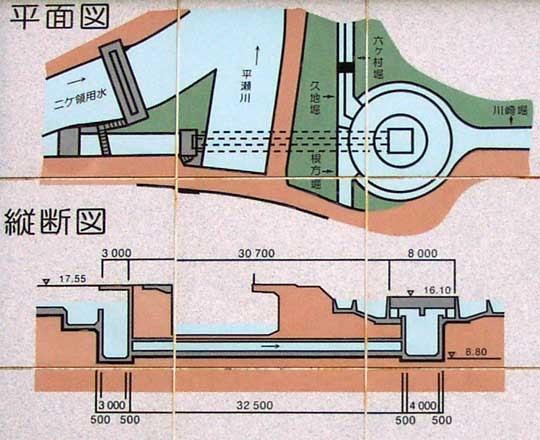

3. Ento-bunsui cylindrical water diversion

The most interesting water infrastructure I’ve seen is the Ento-Bunsui Water Diversion Facility 円筒分水 built in 1941 in Kuji 久地, just south of Tokyo (map). An ento-bunsui is a structure that regulates a river or stream, diverting water towards multiple irrigation channels, which differ in size according to the size of the land they serve. The English word for 円筒分水 is practically non-existent. The best translation is probably “cylindrical water diversion”, but I’ve seen cylindrical water splitter, diversion cylinder, watershed cylinder, and others. I can find no evidence of similar devices outside of Japan.) In Kuji, the ento-bunsui was built to limit flooding of fields by diverting excess water away from arable land and down a separate channel that runs into the Tamagawa river. For more photos of ento-bunsui throughout Japan, do a Google image search for 円筒分水. (Also near here is the Nikaryousui Canal 二ヶ領用水, a wonderful narrow river to stroll along.)

Here’s another one that I’ve never been to, that appears to be in operation today: Shimokuzawa diversion pond 下九沢分水池 in Sagamihara-shi, Kanagawa:

4. Time to hide the water

Some of Tokyo’s best water infrastructure is hidden in plain sight. Beneath the leveed banks of the Arakawa, Edogawa, and Tamagawa rivers are miles of baseball fields, golf courses, and parkland that serve as floodplains for the occasionally tempestuous rivers. In addition to flood control, these wide, green spaces are easily accessible to the cramped residents of Tokyo, providing a backdrop for picnics, dating couples, and amateur musicians.

Other forms of flood control are not as obvious. For instance, it took me weeks to realize this sunken baseball field is an enormous flood basin for the narrow Zenpukujigawa river 善福寺川. The Suginami City website even warns that the field may not be available due to its role as a “regulating pond” 調整池. Details: Wadabori Park 和田堀公園野球場, 〒168-0061 大宮1丁目6番 (map).

Rivers without a taste for baseball can also unleash their excess water on tennis courts, as seen in these two examples from the Zenpukujigawa 善福寺川 (map 1, map 2) and one from the Nogawa 野川 (map 3). Just like a bathtub, the riverbanks have overflow drains that siphon-off water into a nearby tennis court.

See also:

5. When it doesn’t rain, it doesn’t pour

Given Tokyo’s history of flooding and the ever-present rainy season, it can be hard to believe that water has ever been scarce. But as recently as 2012, people were worrying about the water supply after an unusually dry spring. The problem didn’t seem to affect anyone’s daily lives, and it seems to have been solved by a few rainstorms. This was nothing like the shortages experienced during the “Olympic Drought”.

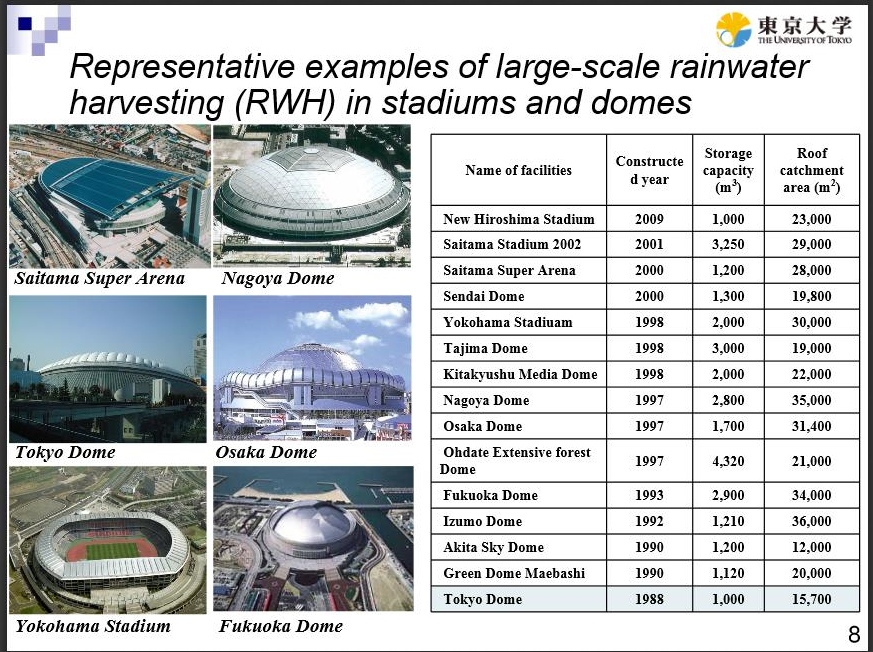

In the 1960s, Japan’s booming economic development, coupled with reduced rainfall in the Kanto region, led to water shortages in Tokyo, leaving much of the city with water for only 9 hours a day. While Japan prepared for its coming-out party at the 1964 Olympics, the capital contended with the unfortunate nickname “Tokyo Desert” (page 159). It was during this time that Japan started to investigate the reuse of waste-water, which can be seen today in a number of creative (and hidden) water collection facilities, including sumo and baseball stadiums.

Such non-traditional sources of water have become increasingly necessary, as average rainfall in Japan decreased by approximately 7% during the 20th century, with larger year-to-year fluctuation (page 3). In an interesting footnote to the drought of 1987, the body of a missing teacher was found at the bottom of the dried-up Shimokubo Dam reservoir 下久保ダム.

I haven’t discovered any dead bodies, but I have encountered some interesting dams, reservoirs, and water storage facilities during my walks around Tokyo, such as the Magome Water Supply Tower 新大田区百景 「馬込給水塔」 in Ota-ku (1951).

Or the Komazawa municipal water tower 都立駒沢給水塔 near Sakurashinmachi 桜新町駅 (map).

Water tower, circa 1931 (source):

And grandest of all is Ogouchi Dam 小河内ダム, home of the Lake Okutama reservoir 奥多摩湖 (1957). (Tokyo Metropolitan Government Ogouchi Dam)

The projects described above differ in scale and purpose, but the unifying theme is the enduring importance of public works and infrastructure. Without effective flood control, Tokyo would annually suffer billions of dollars in property damage. And without water infrastructure, the Tokyo-Yokohama urban area could scarcely hold 37 million people. As I pass by projects that were completed 60, 90, 150, or 400 years ago, I am grateful for the fruits of their labor. As I finish up this blog post I look at the kitchen sink again and think about the 3 glasses of water I’ve had in the past hour. What a miracle.

Also, I really need to use the bathroom.

Postscript

The following section was originally at the start of the post – I’ve moved it to the bottom now that the NGO described below is no longer operarting (I believe).

The Water Cycle & ClearWater Nippon

The water cycle, or hydrologic cycle, is the continuous movement of water on Earth. Unlike earthbound minerals such as oil or gold, water rises into the air, travels vast distances, and ignores the political boundaries below. Water is transnational and essential to life. If a country has no oil, we say, ‘too bad’, but if a country has no water, we do something about it. Or at least we should. Who wants to help?

A ClearWater well user:

One organization lending a hand is ClearWater Initiative, a US-based nonprofit that has helped provide access to clean drinking water to roughly 30,000 people in over 40 villages in northern Uganda ウガンダ. In Japan, ClearWater is represented by its sister organization, ClearWater Nippon クリアウォーター日本. I first learned of ClearWater in 2012 when I met Alice Wei, Chief Operations Officer and Founding Member of ClearWater Nippon. A week after meeting Wei I attended ClearWater’s Thanksgiving dinner/fundraiser, where adjectives like ‘satisfying’ and ‘inspiring’ filled me head. It was the turkey that was satisfying; it was the event’s programming that was inspiring.The highlight of the evening was a Skype conversation with a team of ClearWater staff/volunteers in Uganda who shared an update on their current project. This was an effective personal touch consistent with ClearWater’s mission, which has always been personal.

ClearWater Initiative was founded by Benjamin Sklaver in 2007. It was formed from Sklaver’s experience as a civil affairs officer with the U.S. Army in northern Uganda, where he helped build roads and wells in areas harmed by conflict. Benjamin was killed by a suicide bomber in Afghanistan in 2009, but his family, friends, and colleagues have carried forward with his vision for ClearWater. One of these friends is David Abraham, a natural resource strategist who had overseen ClearWater’s operations in Uganda. In 2011 Abraham brought ClearWater to Japan when he was a visiting scholar at Japan’s Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) and also a fellow at Tokyo University’s School of Public Policy. Today, Abraham remains the chairman of ClearWater Nippon, and operations in Uganda are overseen by Sunday Ojara, ClearWater’s Country Manager.

A primary goal of ClearWater Nippon is to develop stronger ties between Japan and Uganda via education, outreach, and the participation of local communities. They have made considerable progress, despite Japan’s reputation for being indifferent to non-profits/NGOs and for having low rates of giving. ClearWater Nippon has a growing relationship with Rikkyo University 立教大学, with students becoming actively involved in organizing ClearWater Nippon events. Coincidentally, I noticed that ClearWater Nippon’s next event will be held next week. In addition to students and faculty from Rikkyo University, the event will be attended by First Secretary Edith Namutebi Nsubuga from the Ugandan Embassy. Event Details:

ClearWater Nippon’s 1st event of 2014 / ClearWater Nippon チャリティーパーティー

- Tuesday, February 18, 2014 / 日時:2014年2月18日火曜日

- The Pink Cow / ピンクカウ / http://www.thepinkcow.com

- 5-5-1 Roppongi Roi Bulding B1F, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-0032

- 場所:ピンクカウ (The Pink Cow)六本木店 東京都港区六本木5-5-1 六本木ロアビル B1F

A belief in the importance of personal involvement is built into ClearWater’s DNA. In Uganda, ClearWater’s projects are built around the active cooperation of villagers. All projects start with community training, focusing on sanitation, water source maintenance, and financial management. Training takes up to five months and includes extensive site surveys and community interviews. Villages must then meet benchmarks before ClearWater proceeds with project installment. Communities must establish an oversight body for the water point and show they have the financial ability to maintain the water source. Villages also are required to pay for a portion of the project and physically help construction as needed. This approach has helped communities take responsibility for ongoing maintenance and has fostered a greater appreciation of the importance of their drinking water source.

Notes and Resources:

Introduction

- (A) Public-health initiatives led by the Americans in Japan after WW2 are described on page 509 of the excellent American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880 – 1964 by William Manchester.

- the tokyo files: rivers & green roads 東京の川や緑道: River Glossary

1. Tamagawa-josui

- (B) Along the canal, one of my favorite spots in all of Tokyo is here, just south of Takanodai station 鷹の台駅. This modest junction contains tall trees, a park, the canal, a train, and a dirt path; just 32 minutes from Shinjuku station, it is both quiet and connected, the essence of why I treasure Tokyo neighborhoods so much.

- A portion of the Tamagawa-josui is subject to a land-use debate; see: The Kodaira Referendum: fighting for Democracy in the Acorn Forest

- Tamagawa Josui: Edo’s Water Supply (NAJAS Edo tour) – broken link: us-japan org/edomatsu/josui/frame html

- Tamagawa-josui: water for thirsty city (now a restricted link)

- 上水散策・近道お楽しみコース(分岐コースあり) (detailed instructions for walking along the Tamagawa-josui)

- 多摩川探訪 Tama River exploring: wonderful photos & text about the Tamagawa river

- Water sanitation in Japan (Wikipedia)

- Another notable irrigation system: 六郷用水 Rokugo yōsui, which has influenced street patterns in Ota-ku

2. Steep rivers – the red sluice gate

- Great background on the 1910 flood

- Arakawa Museum of Aqua (near the Red Sluice Gate) 荒川知水資料館(通称:アモア)

- Akabane Station, Kita-ku & Iwabuchimachi: water, tunnels and liberty

- Akabane-Iwabuchi area guide (Tokyo-Tokyo.com)

3. Kuji ento-bunsui / ento-bunsui in general

- Address: 1 Chome-28-7 Kuji, Takatsu-ku, Kawasaki-shi, Kanagawa-ken / 1丁目久慈、高津区、川崎市、神奈川県 (map)

- Step-by-step pictures of how the water is distributed: 円筒分水(川崎市高津区)

- Ento bunsui: Shimokuzawa diversion pond

- Nikaryo waterway canals: excellent discussion of the Nikaryo-kumiai-coop system

- 久地円筒分水 Kuji entō bunsui

- Kuji ento-bunsui (Japanese Wikipedia)

- Entō bunsui 円筒分水: Japanese Wikipedia

- Entō_Bunsui: German Wikipedia

4. Flood

- Of related interest, “How giant tunnels protect Tokyo from flood threat“

- River embankments and floodplains 堤防と氾濫原

5. Drought

- “Significance of rainwater and reclaimed water as urban water resource for sustainable use” (2012), Hiroaki FURUMAI, Professor, Research Center for Water Environment Technology University of Tokyo

- “Welcome to the Tone Canal Project”

- “Outline of Tone Canal Project”

- Tokyo Waterworks Map 東京都水道地図 and Murayama-shimo dam 村山下ダム

- LARGE-AREA AND ON-SITE WATER REUSE IN JAPAN”, Yutaka Suzuki, Masashi Ogoshi, Hiroki Yamagata, Masaaki Ozaki, Takashi Asano (broken link)

5b. Komazawa municipal water tower 都立駒沢給水塔

- 駒沢給水所 Komazawa water supply station (Tokyo Metropolitan Government)

- 駒沢給水塔風景資産保存会 Komazawa water supply tower landscape asset preservation party

- Photos: 駒沢給水所に行ってきた I went to the Komazawa water supply station

[…] Splashing around Tokyo’s water infrastructure […]

A fantastic article, Clark. I’ll be creating a unit on Tokyo water infrastructure for my secondary school students and will be referencing your article for them to read and learn from.

[…] Splashing around Tokyo’s water infrastructure […]